When Jack and Bob Ingham outlined their plan to establish a racing and breeding operation from the ground up, there was no blueprint – at least not within racing – but the chicken farming empire they had built provided the template.

In the 1950s, Walter Ingham Jr inherited a small farm at Casula, NSW, from his father and turned it into the most successful chicken farm in the state. Within another generation, his sons Jack and Bob had transformed the 42-acre farm into Inghams Enterprises, a $2 billion per-year business that employed more than 8000 people across 100 different locations.

In the mid-1980s, the Inghams had set about revolutionising racing and breeding in the same way they had the poultry business. The brothers were already successful owner-breeders, but this was to be racing on an industrial scale.

“Nothing like it had been set up of that size in Australia and it had been their dream to do it,” says Trevor Lobb, who was lured from William Inglis to oversee both the racing and breeding operation. “The success that came was from the ability to dot their i’s and cross their t’s.”

To understand what the Inghams built, and how, it is important to know who they were. Talk to the people who knew the brothers well and you wonder how they worked so closely together, given how different they were.

Jack, who passed away in 2003, was a racing tragic who wore his heart on his sleeve. They reckon the midweek Canterbury races couldn’t start until he arrived. Perhaps that was said in jest, but we will never know because Jack was never late. Bob, who died in September, was more reserved. He loved racing just as much, but was a pragmatist, a facts-and-figures man who tallied every cent and produced a ledger for everything – even the brothers’ betting – on June 30 each year.

The brothers went halves in everything, even wins and losses on the punt. “I paid for three of Jack’s divorces … or half of them,” Bob joked in a 2008 interview with commentator John Tapp. True to their personalities, as a punter Jack worked on a day-to-day basis, or even race-to-race, as he rode the emotional highs and lows, but to Bob – who was considered and discrete with his betting – the end-of-financial year ledger was everything.

Initially, the brothers operated from adjoining desks in a Liverpool office that had a single telephone line, and sometimes used their similar-sounding voices to streamline their communications with customers. “Somebody would ring and they’d be talking to Jack. I could pick up my phone and listen in, and then Jack would stop talking and I would carry on,” Bob recalled to Tapp. “They would still think they were talking to Jack.”

According to Lobb, even when they got their own offices “it didn’t matter”.

“When you went up there they were always together. They had their ups and downs, but they never showed that. They worked things out and, once a decision was made, it was getting done.”

When applied to racing, the brothers’ fine-tuned business acumen and famous attention to detail, infused with a passion for the sport, proved to be a dynamic combination. They set a benchmark for on-track performance – paving the way for the mega-stables of today – and through their breeding, created a legacy that lives on through the bloodlines of some of Australia’s best racehorses.

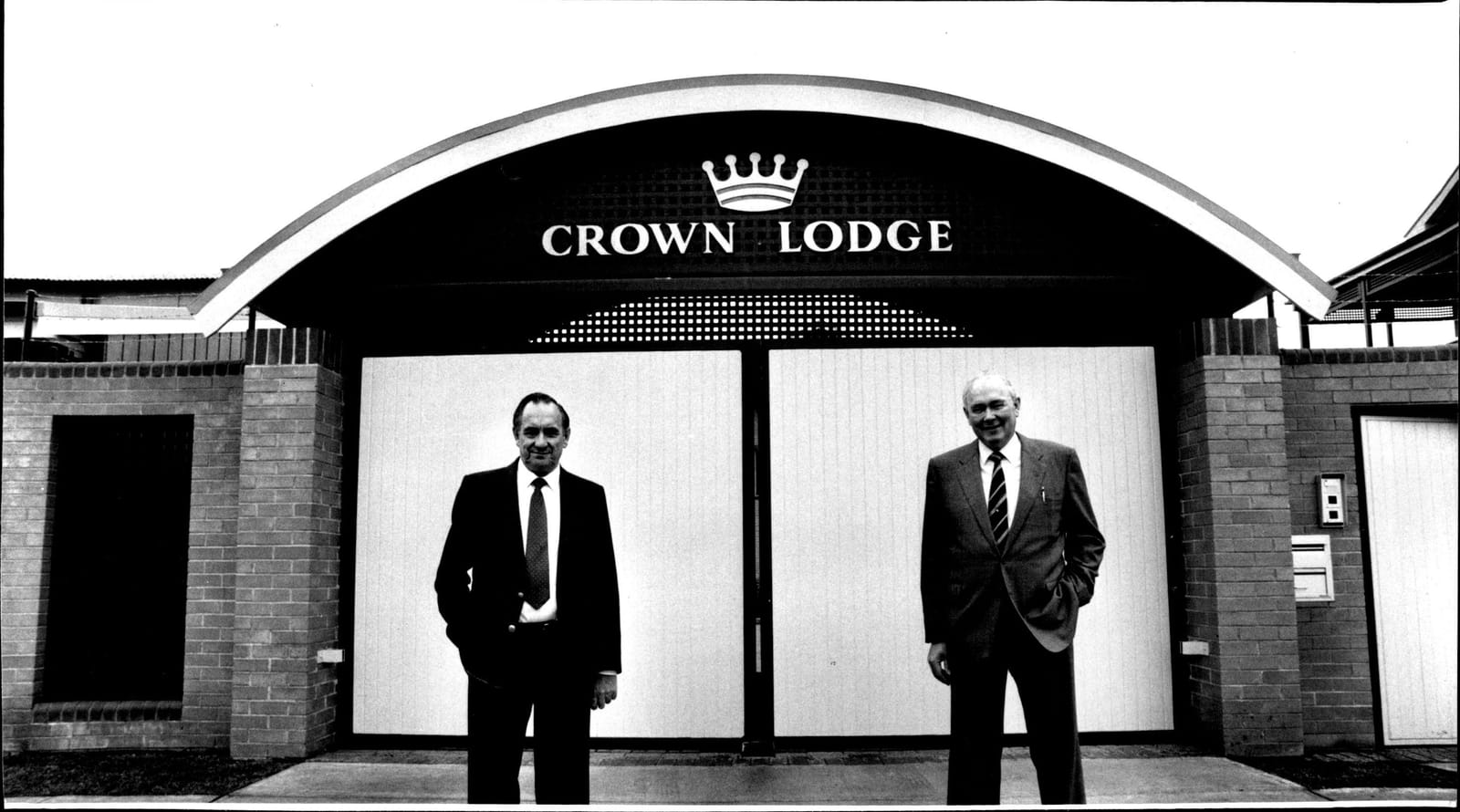

It all started with a budget of $35 million and two city blocks at Warwick Farm, including a 35-horse barn that would become Crown Lodge. Then there was a farm for stallions and broodmares, Woodlands Stud near Denman in the Hunter Valley. A pre-training centre at Belmont Park completed the “from stud-farm-to-stables” production line.

“Nothing like it had been set up of that size in Australia and it had been their dream to do it” - Trevor Lobb

It was Bob Ingham’s meeting with American poultry boss Don Tyson that sparked a rapid growth in the chicken business when the brothers applied new processing and packaging techniques. Those lessons learned – how to minimise costs and maximise output, without compromising quality – would now be applied to racing.

Ingham Racing would be an arm of Ingham Enterprises – just like the chicken farms and plants – and would be run with the same scrutiny and sophistication; big on infrastructure, numbers and streamlined systems. Only the best staff are sought.

Bob, ever the numbers man, wanted more than 100 horses in work at Crown Lodge, but the facility would not cut corners. Everything from the size of the boxes (20ft by 12ft – eight feet longer than a usual box) to the direction most boxes faced (north-south, to ensure maximum comfort from a cool breeze, rather than the hot westerly that can blow through summer) was in line with the Ingham philosophy of “doing things for the right reasons, and doing things the right way”. No expense was spared. There were thick doors to maintain warmth in winter, and a tunnel connected the stable to the racecourse to avoid road crossing.

The stables could have been developed anywhere, but the brothers stayed where their hearts lay. “They were boys from the west and they never lost that,” says Lobb.

Jockey Rod Quinn, who was retained by the brothers under trainer Vic Thompson, was stunned at the scale of the operation springing up around him and at the calibre of horses being purchased by Lobb. “I knew they were serious about what they were doing when I saw the type of horses walking into the yard,” Quinn says.

Then there was the system, implemented by Thompson and then fine-tuned by John Hawkes. “It was a well-oiled machine and ran like clockwork,” Quinn says. “It was a really great place to work as a jockey. We just went out in the middle of the track and waited. We had a lot of very good staff; the horses arrived already warmed up and we could work 15 or 20 horses in an hour.”

When Hawkes replaced Thompson as head trainer in 1991, it signalled the start of a golden era that can be best summed up in names and numbers. The names include some of the greats of the turf. Any mention of the Inghams starts with Octagonal and spitting image-son Lonhro, but also a string of top-class gallopers, such as Arena, Freemason, Viscount, Yell, Unworldly, Niello, Commands and Strategic. And the numbers: Hawkes trained more than 4000 winners during his 15 years in charge, including a staggering 493-1/2 Group race wins, 82 of them at top level.

In 2001-02 Hawkes broke the Commonwealth record for the most wins in a season with 334. It was part of a 13-season run during which the stable had at least 250 winners in each term and topped 300 three times.

The operation eventually expanded to include 50 horses at Carbine Lodge in Melbourne, plus 30 horses at Tenor Lodge in Brisbane and another 25 located at Toltrice Lodge in Adelaide, and the cerise colours – and the black second set – could be recognised far and wide.

“The highs were amazing,” Hawkes reflected when his time with the Inghams ended in 2007. “Within three years of training for the Inghams, we were flying around in Learjets, hopping from state to state, winning Group One races – it was like Hollywood. An experience I’d never felt.”

“It was years ahead of its time,” Lobb says. “Now you see [Chris] Waller and [Ciaron] Maher, and the bigger stables have become bigger and bigger – but it all works through the infrastructure of it all. Those systems can’t work without the infrastructure and that is what Bob and Jack understood from the start. It was a huge operation, but because Bob was such a stickler for facts and figures it worked.”

“It’s all genetics,” Bob Ingham once said. He was talking about chickens. “If you match them right, it makes the chicken grow quicker and they eat less food,” he added. But he could easily have been talking about the art of breeding thoroughbreds.

The brothers’ first Group One win was with a homebred, Sweet Embrace, who scored an upset victory in the 1967 Golden Slipper. She was the granddaughter of a well-bred but unsound mare Valiant Rose, gifted to Jack and Bob by their uncle Bert Stanton.

The Inghams possessed a big enough chequebook to fill Crown Lodge with sales-topping colts, but they wanted to breed their own and Lobb had been tasked with sourcing fillies and broodmares to stock Woodlands. Soon there was another farm at Cootamundra and that budget of $35 million was starting to look like small change, and Bob’s ledger was looking more than a little lop-sided (he later revealed the outlay had blown out to $286 million spent in the first 10 years of operations).

“When they first came to me they said, ‘We’re going to get a couple of stallions and race a few.’ But we ended up with 1500 horses” Lobb says. “They did it because they could, and they could fulfil a dream they’d had since they were teenagers”

Crown Lodge ran with military precision, but it needed soldiers – and that was the role of Woodlands Stud. Bob wanted 200 two-year-olds ready to go into training on August 1 each year. The stable dominated the two-year-old ranks, particularly through the middle to late 90s.

In 1996-97, the stable had 95-1/2 two-year-old wins and more than 600 overall between 1992 and 2008. They were dizzying numbers, but quality wasn’t compromised, and that juvenile success included five more Golden Slipper winners to go with two won before the Crown Lodge era.

It’s difficult to pick one high point from such a sustained stretch of excellence. However, from a breeding perspective, Lonhro – a champion racehorse and then champion sire – might be it, and he showed that those numbers didn’t come at the expense of quality.

Born December 10, Lonhro’s brand – 344 over 8 – means he was the 344th foal born at Woodlands that year, and the ‘8’ represented the 1998 breeding season.

Conventional racing wisdom dictates that December foals can’t do what Lonhro did, especially in Australia where the predominance of two-year-old racing places a premium on precocity. Despite the late foaling, Lonhro won a Blue Diamond Prelude and dominated the Caulfield Guineas before his third birthday. Lonhro went on to win 26 races from 35 starts as Bob Ingham raced his prized stud prospect on – his extraordinary Australian Cup victory was as a five-year-old – despite huge offers to sell.

“We were lucky we were in a position by then to knock those offers back,” says Lobb. “We knew what every horse had cost from birth and how much it returned. That meant we knew which lines were working and which ones weren’t. That was how we did it. There were a lot of horses, but there was an accountability to what we were doing.”

“Within three years of training for the Inghams, we were flying around in Learjets, hopping from state to state, winning Group One races – it was like Hollywood. An experience I’d never felt” - former Crown Lodge trainer John Hawkes

Close friends are adamant that had Jack still been alive he would never have sold the operation – it would have broken his heart – but in the end it was, unsurprisingly, a number that caught Bob Ingham’s attention: $500 million.

That’s how much Sheikh Mohammed paid in an all-inclusive, walk-in-walk-out deal that remains the biggest of its kind in racing history.

Bob Ingham didn’t leave racing – no amount of money could buy those iconic cerise silks or diminish his passion for the sport – he continued to invest in yearlings and race with Chris Waller.

Now, even after his death, the family legacy continues to run deep through the sport. Ingham’s daughter, Debbie Kepitis, was a part-owner of Australia’s greatest racehorse: Winx. A mare whose incredible winning streak made the horse “public property” in the same way Lonhro had once captured racing fans’ imagination. Bob’s son John was a vice-chair of the Australian Jockey Club.

And the brothers' famous cerise silks remain an important racing accessory for the extended Ingham family.

Fangirl won in the colours when she swept to victory in the King Charles Stakes III at Randwick during the Sydney spring carnival.

Fangirl carries the cerise silks to victory in the inaugural G1 King Charles III Stakes 👑 @cwallerracing @mcacajamez @DKepitis @WoppittB pic.twitter.com/pHk9ivKKMJ

— Australian Turf Club (@aus_turf_club) October 17, 2023

Those who oversaw the stable’s rise – Hawkes and then Peter Snowden – have moved on to start successful stables of their own, but will forever be associated with Crown Lodge.

Godolphin has made many changes since the purchase – a training centre at Agnes Banks in the Hawkesbury, moving the stallions to Kelvinside, and the importation of European sires and broodmares has given it a more cosmopolitan feel – but the Warwick Farm stables remains a nerve centre and Crown Lodge continues to churn out winners.

It’s the base for Godolphin’s two-year-olds and the systems put in place during the golden era remain largely the same.

The bloodlines of many of Sheikh Mohammed’s winners run thick with Woodlands history, too. When Godolphin produced the Golden Slipper trifecta in 2019, the winner, Kiamichi, was a filly out of a Woodlands-bred Canny Lad mare. The runner-up was Microphone – descended from three generations of Woodlands mares – and in third was Lyre, a filly by Lonhro and granddaughter of the Inghams’ 2005 Thousand Guineas winner Mnemosyne.

Champion jockey Darren Beadman created many memories in the cerise silks as first-choice rider for the Inghams, and now his career has come full circle. As assistant trainer at Godolphin he spends each morning at Crown Lodge.

“It still has that Jack and Bob feel about it,” Beadman says of the stables. “The colonial bloodlines are still coming through as well. I get a thrill out of seeing a horse like Impending, who is by Lonhro and out of Mnemosyne, succeed.”

Beadman notes the number of people who worked under the Inghams that are at Godolphin after nearly 30 years – and the way they go about their work – is a sign of the Ingham influence.

“They were down-to-earth and looked after staff,” he says. “Bob lived by the Ingham philosophy: ‘doing the right things and doing them right’ Mr Bob and Mr Jack’s influence is still strong.”

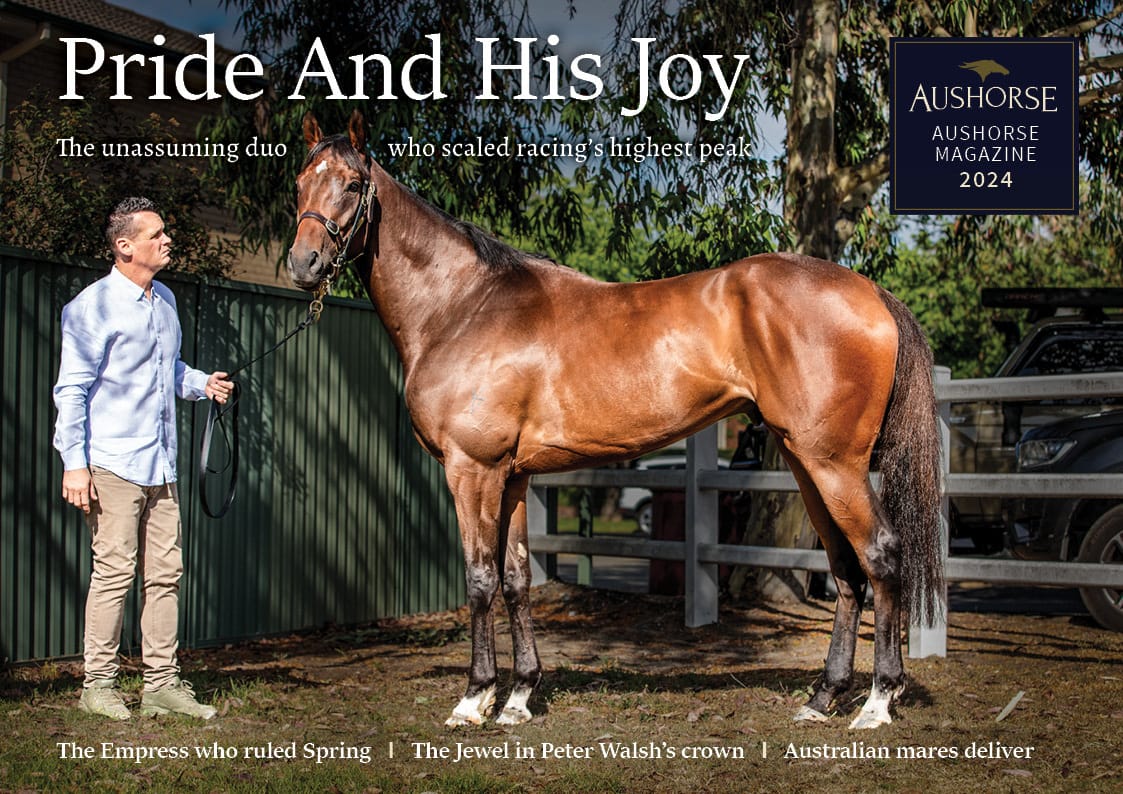

The article was written for a previous edition of the Aushorse magazine and has been republished with permission. The 2024 edition of the Aushorse magazine is now available.