‘The one constant in their life’ – The unbreakable bond between horse and strapper

Donna Fisher cried for two days straight when she realised Black Caviar’s end was near. The strapper and the unbeaten mare shared an unbreakable bond during her racing days, a relationship mirrored with champion racehorses and their strappers the world over.

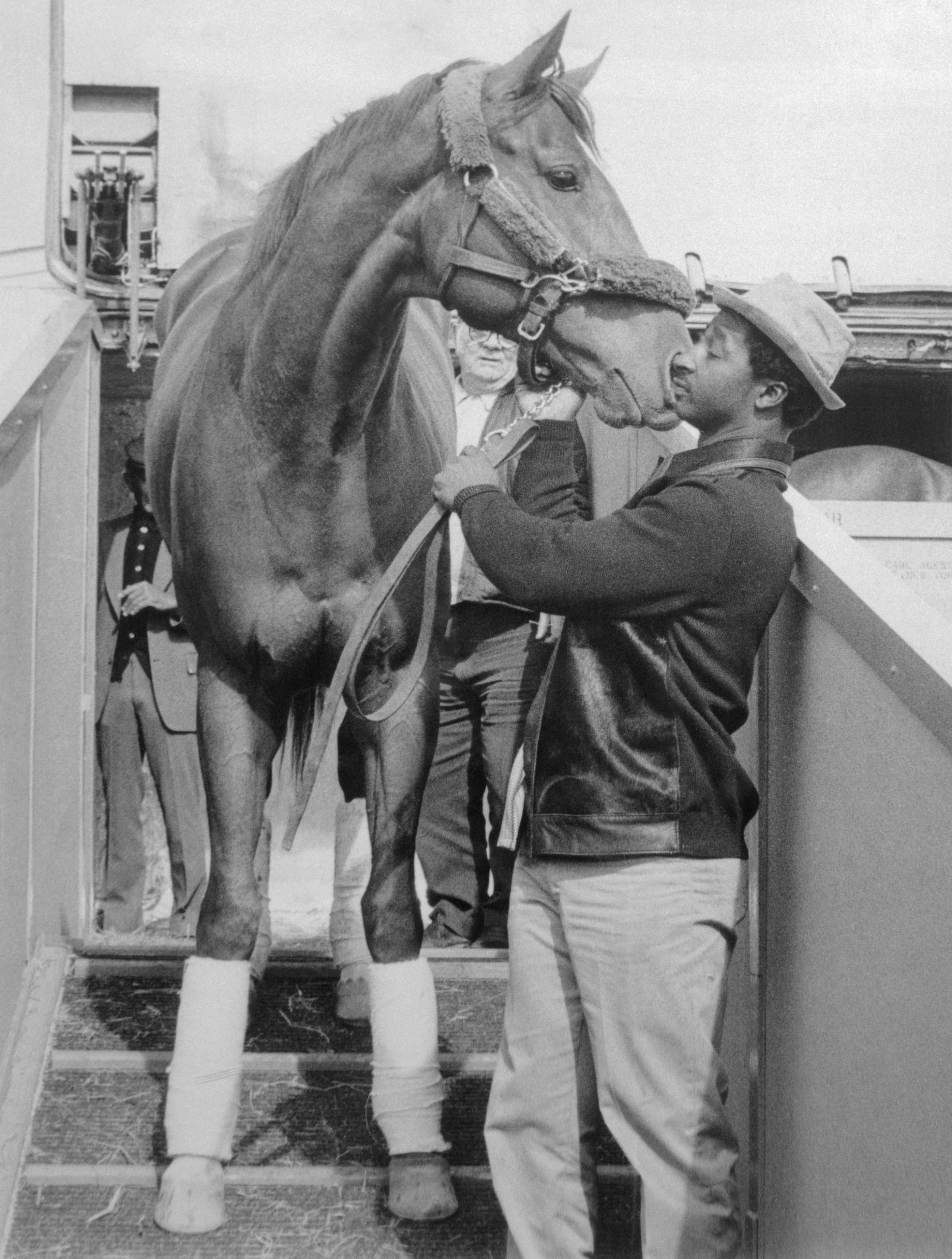

In 1997, a US magazine called Western Horseman ran a story on Secretariat which featured a group photo taken the day Secretariat won the 1973 Kentucky Derby.

The caption identified the trainer, horse, owner, and even the owner’s sister, but the black man clutching Secretariat’s bridle was merely an “unidentified handler”.

That unnamed groom was Eddie “Shorty” Sweat, whose relationship with Secretariat was as invisible as it was intimate. However, Secretariat became so famous that even Sweat, the unidentified man, briefly became a celebrity. For a groom, this was an unusual thing.

In early 1970s America, the anonymity of the men who groomed the great racehorses was accentuated by racial division. Grooms were mostly black and from impoverished backgrounds.

Sweat slept outside Secretariat’s stall on race-day and spoke to the horse constantly in the Southern Creole language of his family. Horsenetwork wrote that Sweat “grew up a black man at a time when hired help didn’t look (their employers) in the eye”.

As horsenetwork explained in 2022: “History books have always recorded the deeds of great horses, their valiant riders, and benevolent owners. But the stories of grooms are less known. The groom, so often, is the first to be forgotten.”

Few horse statues feature the humble groom, the race-day cameo actor who escorts the champion into the mounting yard and escorts it out as focus turns to the delighted owners and their hangers-on.

The endless hours of care and companionship, away from the buzz of the winner’s stall, away from the glamour of race-day, are wiled away mostly in darkness.

So, it was remarkable that some years after being described as “unidentified handler”, Sweat was immortalised in bronze, with Secretariat, at the Kentucky Horse Park.

The death of Black Caviar, another horse commemorated in bronze, hit hard.

Those who had been closest to the gentle galloping machine wept for days. Two people had been closer to “Nelly” than Peter Moody: his foreman Tony Haydon and the mare’s strapper Donna Fisher.

Moody cried for an hour in his car when he learned Black Caviar had succumbed from laminitis.

I rang Haydon, who now trains in Queensland, for some words and half-way through he choked up and said ‘I’ll have to ring you back’, which he did.

I then rang Donna, who now straps for Kelly Schweida in Brisbane, and she seemed OK.

“I’ve done all my crying. I cried for two days straight,” she said.

Love. That’s the essence of the horse and strapper relationship according to Greg McLaren, who was foreman to Bob Hoysted during the Manikato era.

When McLaren speaks of the dedication of strappers to all horses, he remembers freezing winter mornings at Mordialloc beach. Hoysted had two champions at the time, Manikato and Scamanda.

“For three months with Scamanda we were in the water barefoot in shorts and t-shirts. This is June/July. It was freezing. Scamanda had ‘hot’ feet and we nursed and nursed him and he came out and won the Moondah Plate,” McLaren said.

McLaren, who has lived in Kuala Lumpur for many years and is still involved in the equine industry, said Rosalie Maber – a woman as anonymous as Eddie Sweat – was the unsung hero of the Manikato story.

“She rode the pony Shiloh. Ricky McLeish usually rode Manikato (in trackwork) but Rosie had to deal with all the shit “Kato” could throw at her. He was a very strong-willed horse yet Rosie had a special relationship with him,” he said.

“In history, it’s usually only the trainer and jockey who get recognised but the team behind them means so much. I’d like to see Rosie get recognised.

“For Rosie, for all of us back then, it was the love of the horse. Walk on broken glass, stand in front of a train, that sort of love.

“We grew up when the horse came first and you came second. If you had a big night, which wasn’t very often, you were still there at 4am.”

When Manikato was ailing and close to death, concern for the champion was widespread. Miracle cures arrived by mail. Holy water arrived from Lourdes in France.

“I also remember some Indian concoction,” McLaren said. “Sadly, the horse still died.”

McLaren said that the strapper sometimes added a layer of romance to the great racing stories.

“You look at Tommy (Woodcock) and Phar Lap. Tommy became part of history. Just like Seabiscuit in America, Tommy and Phar Lap became Great Depression heroes,” he said.

While Sweat is commemorated in bronze in Kentucky, Woodcock is probably the only strapper in Australian history to play such a central role. Woodcock shielded Phar Lap from bullets and cradled the horse as he drew his last breath.

He also helped shape the mystery of Phar Lap’s death in California. The strapper became a storyteller.

In 1936, Woodcock provided Brisbane’s The Courier Mail with explosive revelations about Phar Lap’s demise. Woodcock spoke of a mysterious American gangster called “The Brazilian”, who Woodcock had seen multiple times in the vicinity of Phar Lap, including near his stables in Mexico.

“His life was in danger from the moment he landed in America,” Woodcock said, adding The Brazilian “had the reputation of being a killer”.

The Brazilian and his hoods were on-track in Mexico the day Phar Lap won the Agua Caliente Handicap, Woodcock claimed.

Woodcock fuelled the myth that Phar Lap was killed by gangsters hired by American bookies. “How my blood boils to think how little such a noble animal meant to the gang that sentenced Phar Lap to death. I can’t figure it out.”

Woodcock was known to spin a tale and science says Phar Lap succumbed to bacterial infection.

The lingering image of Woodcock and Phar Lap was of love and dedication. They had a bond not unique to them but unique to horses and their closest carers. It’s a relationship Haydon says is “hard to explain”.

“It’s like people. Some get on, some don’t. Strappers become good mates with their horses,” he said.

Fisher remembers Black Caviar as a gentle mare but one with limited tolerance. She loved “little people”.

“She didn’t like anyone standing over her but she loved kids,” Fisher said.

“We took her to Caulfield after she was retired and a lady there had a son in a wheelchair. He was a quadriplegic. She asked if Nelly could come a little closer to her son and Nelly just gently stepped forward and put her head in his lap. The mum couldn’t hold the camera because she was crying so much.”

Fisher said she and Black Caviar had trust in one another.

“She was so prone to injury that in the early days I was mostly in charge of her medications and she just knew that I was there to help her,” she said.

When Claire Bird learned of Black Caviar’s death, her first thoughts were for Haydon and Fisher.

Bird, who now works for Tony Gollan in Brisbane, was the strapper of the immortal Sunline.

“You get so attached to the horse, it’s like losing a child,” Bird said.

“It’s like people. Some get on, some don’t. Strappers become good mates with their horses” – Phar Lap’s strapper Tommy Woodcock

The more time Bird spent with the temperamental Sunline, the more they bonded. They travelled the world together.

“You spend so much time with them you can’t help but fall in love. You spend more time with them than your friends and your partner. They get anxious when you’re not there. They know that you are the one constant in their life,” she said.