Written in The Stars – Neil Kearney on racing’s lost romance

For four decades, Neil Kearney used his ‘gift of the gab’ to tell racing’s greatest stories. He tells Jessica Owers how racing’s narrative changed for him and reflects on the characters and legends that made his job as a storyteller all the more enjoyable.

Neil Kearney was like disappearing ink, for 40 years a storyteller and then he was gone.

“I’d been with Channel 7 for twenty-something years,” he tells The Straight. “We had a fantastic racing team, and there is still a fantastic racing team.

“But I was drifting out of it. I had felt in recent years that racing had become all about the money, not that it hasn’t been about money for the last 200 years. But it felt to me like it was now very much about massive amounts of money and massive amounts of theatre and colour and greed.

“From my point of view, I didn’t want to spend my time on television talking about the odds or the punt.”

During COVID, Kearney drifted quietly out of the Channel 7 racing team. He had been its key storyteller with an enchanting voice, a tuneful way with words and an obvious passion for the sport.

The network, he says, had been respectful of his eccentricities because “I gave the coverage a little bit more soul. Racing, for me, was a platform for telling a lovely story,” but as the pandemic swept through Australia, racing didn’t feel like home to Kearney anymore.

“Racing changed dramatically with the passing of Bart Cummings,” he says. “I think everyone expected his death to be a loss, but for me it took away one of the greatest characters in the history of the Australian turf. After that, it just didn’t have the same romance.”

Kearney is only 70, but old enough to remember a golden era of the turf from which few characters remain. One of his great documentaries was on Tommy Woodcock. One of his best friends was Les Carylon; they met every Friday for lunch.

“Les was a huge loss to racing because his writing elevated racing way above its status,” Kearney says. “He could make anyone or anything shine with his words.

“He wrote some great books about Gallipoli and the Great War, but, as a bloke, he was very understated, very quiet and loved a bit of a chat. We’d have a bottle of wine between us and he’d ring me up on a Monday and tell me, oh, that story wasn’t as good as I could have made it.”

Were there compliments bled from the master?

“It made my day if Les just said hello to me,” Kearney says. “I didn’t need compliments from him, and I never looked for any except that I thought the greatest compliment of all was that he chose me as a friend.”

Carlyon died in March 2019, unrivalled in racing prose. On television, Kearney wasn’t unlike him, though he’ll argue the comparison.

“The only thing I’ve ever tried to do is tell the story in my own voice, and the stories tell themselves. I don’t think I ever manufactured anything or tried to make anything up, and I didn’t really have to do anything other than let the people tell their stories,” he says.

Most people will know this isn’t true, that stories rarely tell themselves.

People talked to Kearney, spilled the tea with him, revealed things that only a good interviewer can extract. Across 10 to 15 minutes of recording, Kearney had to pick what was relevant, cut and edit and soundtrack it, write a script for it and then read it with the smoothness of footsteps on wool.

He brushes away the praise.

“We had very good editors,” he says. “They could bring it all together with so much more magic than just the words that I had spoken.”

Kearney’s working life began over 50 years ago in Tasmania. He grew up in Longford, which just happened to have, and still has, the oldest continually used racecourse in the southern hemisphere. As a child, Kearney sold programmes on-course.

Longford, population less than 5000, has batted well-above its sporting weight for such a small place, and much of its demographic was sport-obsessed, including Kearney. When just 16, he landed a reporting gig for the Launceston Examiner and relocated to the island’s northwest coast.

“I loved everything about it,” he says. “It was a great job, and in the days where you would type up on a typewriter and post the pages through, or send them by courier through to Launceston where they put the paper together.

“I think, luckily, I had the gift of the gab even back then, though plenty of others have had it too. If I looked back, I would never do any other job than the one I’ve done for the last 50 or 60 years. I wouldn’t choose to do anything else.”

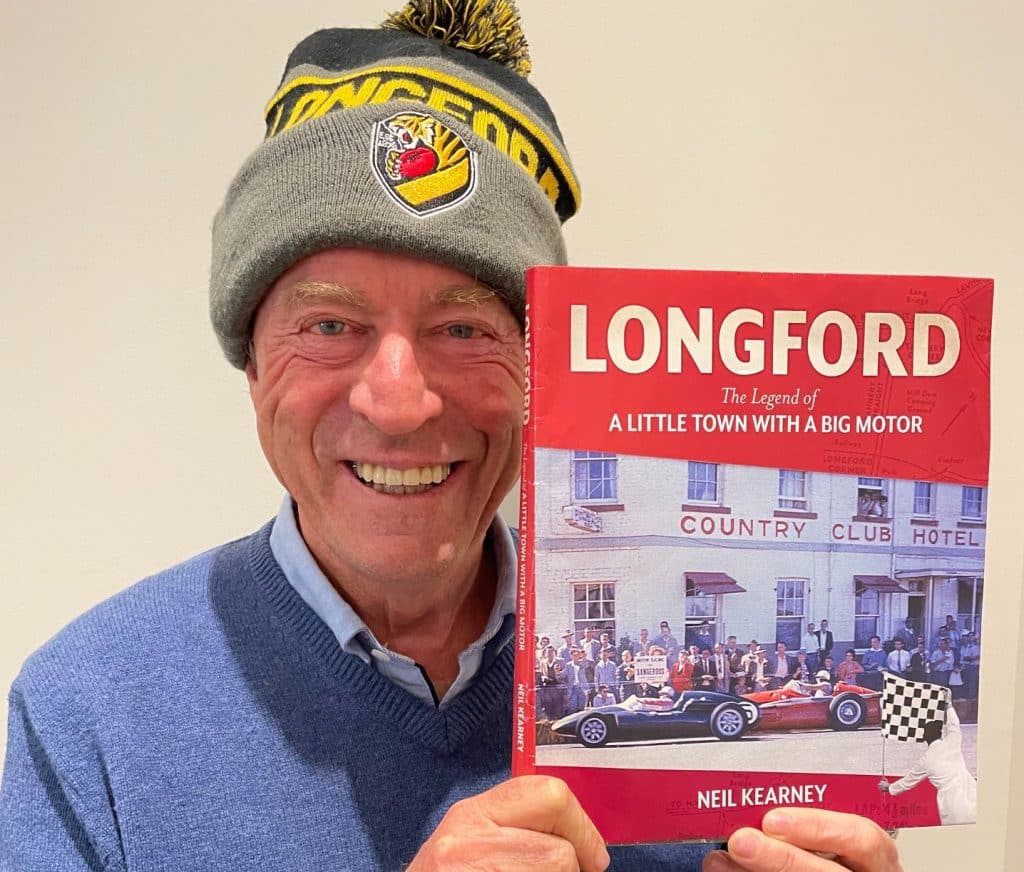

Growing up in Longford was formative. There was horse racing, football, cycling, running and motor racing. In recent years, Kearney wrote a book on the latter.

But when he was about 22, he relocated to the ‘big smoke’ of Melbourne and, eventually, walked into a reporting role on television for Mike Willesee.

“Mostly, I’ve spent my life going back and forth to Tasmania,” he says. “I reckon I have crossed the Bass Strait probably 700 or 800 times the last 50 years. I’m still heavily involved in the football club at Longford, and in various activities down there, but I just as much enjoy coming back to Melbourne.”

Kearney lives between Melbourne and a holiday home along the Great Ocean Road. He is married to Lisa with two daughters, one of them, Annie Kearney, a journalist with the ABC. Like her father, she has covered the Olympic Games, though is far from reaching the 10 Olympics as covered by her dad.

Kearney worked on magazine shows and Sports Sunday across the Nine and Ten networks before landing at 7Racing.

“I mean, to get paid for any of it was just a privilege,” he says, spoken with a vim that suggests he almost would have done it all for free.

“I miss it very much,” he adds. “I’m very envious of Bruce McAvaney still being out there, and Bruce is only a year older than me. But I think budgets don’t permit my sort of magazine stories these days, so it was a great thing to be able to do while we were able to do it.”

Kearney has been missed on racing’s broadcasts. He slid out at a time when the song and story of the athlete were being replaced by the language of wagering. He says that, across all media, economic models don’t seem to allow anymore for strong storytelling.

At Longford as a schoolboy, he was in the same class as author and journalist Martin Flanagan.

“The Flanagan family coincidence is quite remarkable,” Kearney says. “Martin’s father and my father were born one day apart in country Tasmania, and they were both prisoners of war on the Thai-Burma Railway. Both came home to Longford, and Martin’s father was the headmaster at the Longford school for many years.”

“I mean, to get paid for any of it was just a privilege.”

Kearney’s father, Fred, was a shearer, and after the atrocity of the ‘Death Railway’ of 1942-43, he returned to shearing in Tasmania and mainland Australia. He never spoke of the railway, and Kearney describes his father as a withdrawn, mixed-up character.

“Apparently there was some sort of pact that was forced on the men by the government to not tell their families about the stories, about what happened on the Railway,” he says. “My dad was really troubled. He was a decent man, a good man, but he’d hide if people came to visit. He slept on his own in the garage. He couldn’t express his love to my mother, and they never went on holidays.

“But the funny thing about that is that he took me to all those local sporting events and he loved all the things that nurtured my love for sport.”

There is a tragedy in Kearney growing up to be such a storyteller under a father of so few words. Fred Kearney died in a Longford nursing home at the age of 92, born in 1918 and taking his Burma stories to the grave.

When Kearney talks about him, it’s with a tone of voice very different to the one he uses on television. He sounds sad, like it’s the one story he never told.

“As a person, my dad didn’t say much, but you knew there was a lot there,” he says. “He was incredibly tough physically, but he had been affected very badly.”

In 1984, Kearney joined Martin Flanagan and Weary Dunlop, a renowned veteran of the atrocity, at the Burma Railway for a series of articles and documentaries. In fact, Kearney’s wheelhouse wasn’t just sport. It was anything where a story could be told.

It was why he was such good friends with Carlyon and Flanagan, why something in him died with Cummings, and why he edged out of racing when he sensed its soul had been sold.

However, he will admit that racing’s stories have served him.

In 2016 he made headlines when the Irish connections of Heartbreak City, who had just lost narrowly to Almandin in the Melbourne Cup, put him on his backside in the mounting yard.

“They were cheering and jumping around, and they knocked me right over, right on my arse,” Kearney says. “So I’m sitting there and I thought, I can’t do much else now so I’ll get up and tell them they’ve run second.”

He did, but he didn’t know the Irish owners had punted everything to place. They didn’t care that their horse had lost, and pictures of the Australian journalist on the Flemington floor were beamed all over Ireland.

“I don’t think you’ll get any sport or any industry that’s got such a range of colour and theatre and drama,” Kearney says. “People who are crooks and people who are saints, and all of that gets captured and placed into one bag on a racetrack on one afternoon.

“There, you can see so much romance and so much fun and adventure and pain and loss and drudgery. It’s got everything, which is what attracted me to racing in the first place, and why it’s such a great canvas for storytelling.”