Analysis: Are we seeing the end of the small breeder in Australia?

While the top end of the Australian breeding and bloodstock industry remains in rude health, commercial realities are forcing an increasing number of smaller breeders out of the game. Bren O’Brien looks at what is driving this trend and the consequences of this contraction.

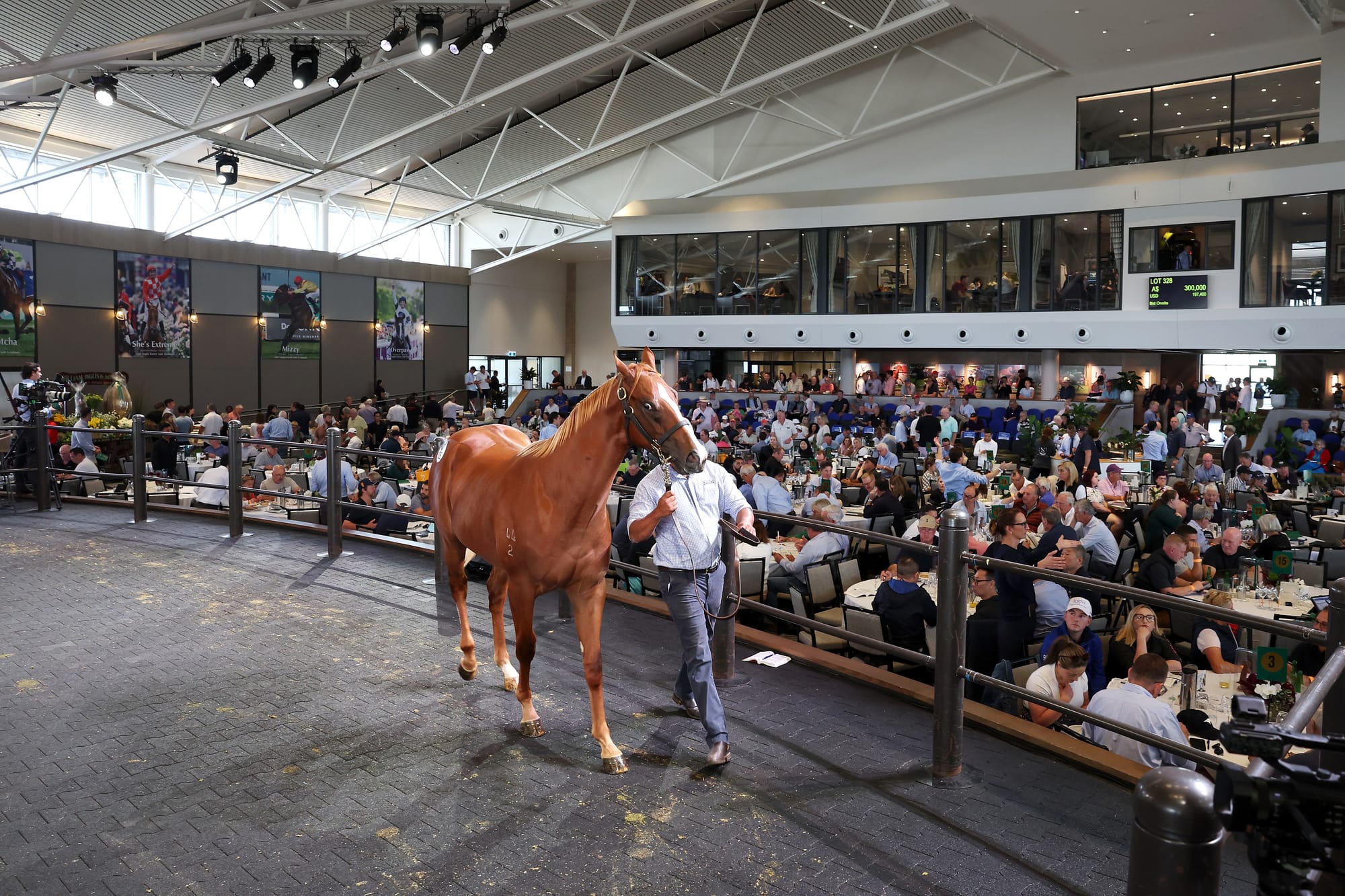

The Hunter Valley’s leading studs will be packed this weekend with wheelers and dealers, dreamers and ‘tyre kickers’ for the annual stallion parades, where studs put their best and brightest on display alongside Group 1 hospitality ahead of the new breeding season, which starts on September 1.

But beneath the anticipation for spring, with its combination of elite racing and new foals on the ground, lurks a cloud of uncertainty. The stallions may look a million bucks, but there is a concern about just how many of them will have full books this season.

It is no secret that Australia’s thoroughbred foal crop has been dropping. It has been for over 30 years, reaching a peak of 23,697 in 1989 with last year’s reported number of 12,362 the lowest since 1977.

Most of this reduction is owed to a more efficient commercial breeding industry. The stats tell us that while the foal crop in Australia has dropped by 30 per cent since 2000, the number of active racehorses has reduced by less than 4 per cent.

However, there are genuine concerns in the industry that the foal crop for 2025, that is those conceived this year, could drop significantly.

That is coming off reports that nominations teams at studs are working harder than ever to get mares to their stallions.

It is not in the interest of studs at this time of year to cry poor when it comes to mare numbers, but several spoken to on background by The Straight are concerned by a sudden drop-off, as breeders reduce their risk exposure to an uncertain bloodstock market.

Smaller breeders were particularly hard hit when selling in this year’s yearling sales, and many have either walked away from their breeding interests or have reduced the number of mares they are breeding.

“The ones with a band of eight mares, are now only sending two or three to be bred with,” one studmaster, who wished to remain anonymous, told The Straight. “Others have decided to get out of the game.”

The issue with the 2024 yearling market was that while aggregates and averages remained historically high, the bottom end of the market did it hard.

There were more yearlings passed in through public auction in Australia, 926, than there have been in a decade. Those at the lower end which did sell, generally sold at a discount.

This was evident at those yearling sales which generally represent this segment of the market.

Inglis Melbourne Gold Sale was down 35.7 per cent on aggregate, Inglis May was down 33.2 per cent and Magic Millions Tasmania was down 29.1 per cent.

Leading industry figures voiced their concerns at the time and, as they battle to get commercial numbers to their lower-profile stallions, those fears have become reality.

So, what has happened to demand at the lower end of the market?

Some point the finger at the proliferation of digital sales, which have become the focus of many medium to smaller trainers, who don’t have the budgets or the risk appetites to tackle the major players at the yearling sales.

There has been an explosion of trading of tried racehorses through this market over the past five or six years. You can understand why these horses appeal to trainers and prospective owners.

It is much easier for them to assess the athletic potential of a tried horse, even via a digital platform. A whole sub-industry has emerged and there are form analysts and agents who specialise in identifying talent from these platforms.

The considerable advantage is that tried horses can get to the track within weeks or months, rather than years. That makes them more appealing to potential owners.

The increased liquidity of that market is also seen as a boon for those taking risks on more expensive yearlings, as they can sell out and minimise their losses should that horse not perform to expectations.

However, the ones who miss out are the breeders, particularly smaller breeders, whose target market, in terms of budget, has been subsumed by the digital explosion.

This trend is particularly evident in places like Tasmania, an industry that suffered a brutal reality check this year. The lack of investment in locally produced yearlings from local trainers has been a concern for some time, but an influx of tried horses from the mainland has compounded the issue.

It is not just broodmare and foal numbers that this has implications for. As we have already indicated, the line at which stallions become commercially viable has become much tougher.

The risk of standing a new stallion is becoming hazardous for smaller farms, and we are seeing a consolidation towards the larger operators, which can operate at scale, and spread risk.

A lot of headlines are written about champion stallions, and commercial juggernauts, such as I Am Invincible and Written Tycoon, but it is worthy to note that both of those started out at very modest prices $11,000 and $8250 respectively.

Stallions kicking off their careers in 2024 at that same price range are among those most under pressure to secure meaningful numbers. Nominations teams know that a book of under 100 for a new stallion would be seen as a black mark on that sire’s commercial prospects in the future.

Nomination fees are always a negotiation, but anecdotally, there has been more dealing than ever ahead of the upcoming breeding seasons. Be it bulk deals or foal shares, studs are using whatever levers they can to get mares to their freshman sires.

“The ones with a band of eight mares, are now only sending two or three to be bred with. Others have decided to get out of the game” – an Australian studmaster’s view on the current breeding industry landscape

But, for some, it is like getting blood from a stone. Having taken such a hit this year, smaller breeders are unwilling to take the risk. Many have already sold out of their breeding interests through the same digital markets, which have overtaken their own yearling market avenues.

Further up the food chain, medium to large breeders are concerned by the dominance of the international market, which is driving an unprecedented number of imported tried horses into Australia. That market, much of it private, is said to be worth anything between $100 million to $200 million a year, and the net impact of that is on the public auction of yearlings.

However, there is little or nothing that can be done to alter this market trend. Some have suggested a welfare levy on imported horses, even a similar surcharge on those that go through the digital market, but another ’tax’ would struggle to get broader industry support. Those digital markets simply support a desire for liquidity.

There is an argument that the digital market has ensured a more efficient model and that horses which may not meet expectations at Sydney or Melbourne metropolitan level get a second chance with other trainers on country or provincial tracks.

That may be the case, but what concerns breeders and studmasters, even those at the top of the commercial tree, is that the diversity of thoroughbred production, which has been such an asset to the Australian industry, is disappearing.

This has other knock-on impacts. Given over 60 per cent of horses are owned in some part by those who bred them, a reduction of the number of breeders would lead to a drop in the number of owners. Again, diversity of ownership is seen as a huge strength of the Australian industry when compared to major markets overseas.

Ownership is a key engagement metric for racing, but similar to breeding, as the costs of racing have increased in the past few years, owners have reduced either the number of horses they have interest in, or the percentages they hold.

It means more horses in fewer hands, which would forever change the shape of the Australian thoroughbred industry.