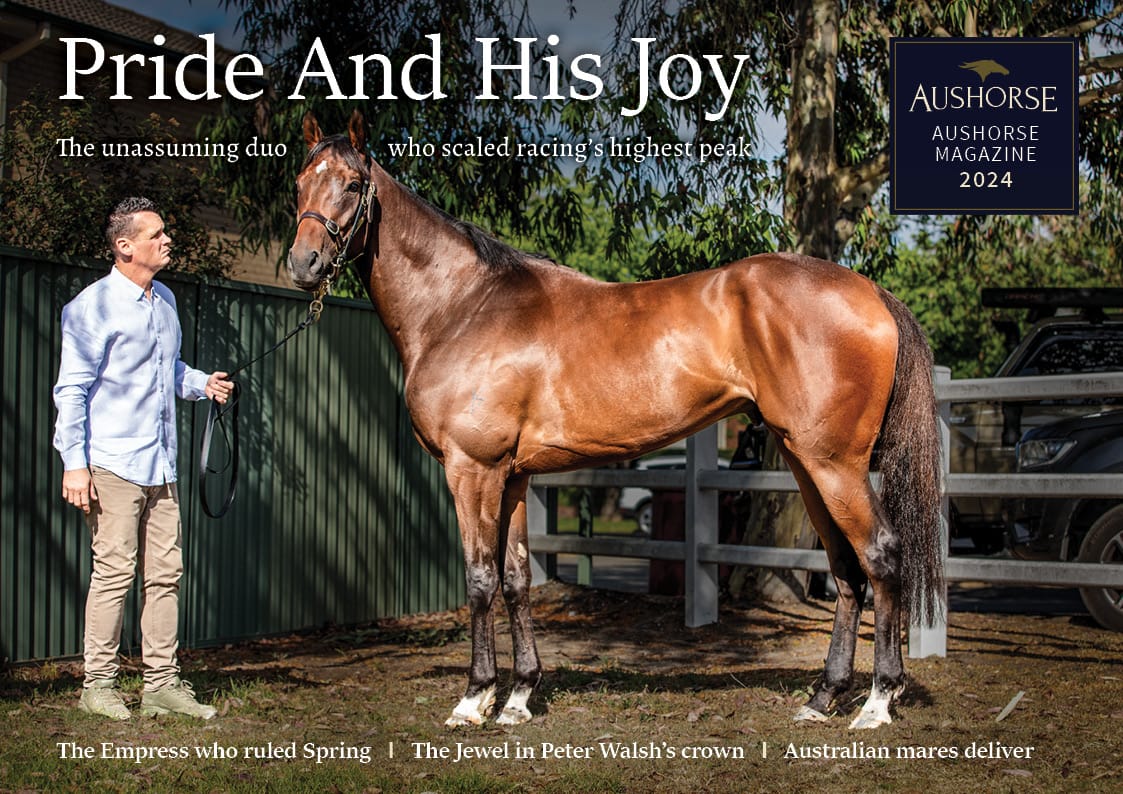

The article was written for a previous edition of the Aushorse magazine and has been republished with permission, with some minor updates. The 2024 edition of the Aushorse magazine is now available.

In his 51st year in horse racing, Gerry Harvey admits he still hasn’t found the answers. Thousands of horses bred, bought, sold and raced, and he cannot say why one wins and another doesn’t.

A daily print-out sits on his desk of the horses he either owns, has owned, has sold or has bred — a thoroughbred with some link to Harvey is on a track somewhere in Australia virtually every hour of every day — and he still says the essence of success is a mystery to him.

“We make a lot of assumptions about what horses are thinking, but they might tell us we were totally wrong,” he offers. “We all wish they could talk.”

He can’t even say why it is that he still gets such a thrill out of seeing a horse win. Half a century hasn’t really enlightened him.

“Why do we get such a kick out of winning? That’s an interesting thought. I see other people get it, and I get it too. There are more important things in the world than watching a horse run across the line first, but why are you so excited about this? I can’t answer the question.”

That’s why the man who knows Australian racing at more diverse levels of involvement than anyone else doesn’t gamble. He never has, and, although he considers it might be something he would do “if I get bored”, he really can’t see himself taking it up at age 84. “I’m not a punter because I’m pretty much going to lose.”

Sitting in his corner office in the headquarters of the Harvey Norman retail empire, Harvey doesn’t come across as someone who takes losing philosophically. His office is filled to the gills with piles of paper, unopened gifts, spreadsheets … and more stacks of paper.

He wears a nondescript branded polo shirt that was probably a freebie, and you could search for a week among all this paper and mess, and you wouldn’t find an ounce of pretension. He says “about a quarter” of the material in the office has to do with racing, but when all the stud books and bloodstock records are added up, it looks like more. His racing manager, Luke McDonald, has an office just around the corner.

In Harvey’s filing cabinet is one irreplaceable, treasured folder of paper. Asked about the first broodmares he bought at Broombee, the farm he purchased in 1972, and Harvey brings out this folder. For fifty years he has listed by hand every single horse he has owned, bought and sold. The ancient yellowing document starts with ‘Roadside Inn $12,000, Scarlet Lane $8,000, Rusty Belle $6,000, Rusty Light $4,000,. Kid Glove $10,000’.

They were acquired at an Inglis dispersal sale, with owner Tom Flynn off-loading stock, and those first five are committed to memory.

“For my twenties, I wouldn’t have been able to name a single racehorse in Australia. But when I got some money (at age 33), I started looking at horses and farms. Instead of buying yearlings, I bought five broodmares. I don’t know anyone else who did it like that. I sold the first three foals as yearlings. One won two or three races, one was stakes placed, and one won 19 or 20 races. I thought, ‘Oh, this is good’ So I kept doing it. I was captured by the racing industry. Why? I don’t know.”

Captured he was. Growing up near Bathurst in New South Wales, Harvey had spent his weekends working on cattle, wool and wheat properties with the ambition of becoming a farmer. He didn’t have a lot to do with horses, nor was he a good rider — “When you’re a kid, you jump on anything and know you’re going to come off” — but he followed racing as a sport, even though his parents showed no interest.

“I was just into racing, I don’t know why. I could have been the local bookie on the train to school. I didn’t bet, but I was happy to take bets.” By his teens, he attended country meetings and memorised recent Melbourne Cup winners.

At the time, he also discovered a competitive fire in all sports, “cricket, tennis, football, you name it. I wanted to play sports every single day. I was okay at everything but not very good at any one. I could beat most people in six sports out of ten, but someone very good would beat me in any one of them.”

Into adulthood, all of that competitive drive and focus went into turning himself from a ‘vacuum cleaner salesman’ into the co-owner of one of Australia’s biggest whitegoods, furniture and appliances retailers, Norman Ross (later Harvey Norman), which listed on the stockmarket in the early 1970s and delivered Harvey what he hadn’t had until then: capital.

He returned to racing with a fervour, buying Broombee, near Armidale, converting it from cattle to horses and racing the champions Gypsy Kingdom and Best Western with his mate John Singleton. He later purchased Baramul Stud and interests in Vinery Stud in New South Wales and Westbury in New Zealand, inevitably adding stallions to his broodmare formula, steadily building a large breeding enterprise.

As a breeder, Harvey says, “I had no guidance whatsoever. I read the catalogue and thought, ‘I know what I’m doing. I didn’t, but I had some luck.” To this day, he says, he works more on instinct than science.

“I’m not sure there’s a lot of expertise in breeding. A lot of other people are sure there is. How much is cause and effect and how much is accident?”

He points to the extraordinary story of Giga Kick, the winner of the 2022 Everest — unfashionably bred and having survived a life-threatening bout of colic — the gelding wasn’t considered a commercial sale prospect and was instead retained by his breeder, but there are thousands of stories like it.

“I’m not sure there’s a lot of expertise in breeding. A lot of other people are sure there is. How much is cause and effect and how much is accident?”

“Every rule is made to be broken. People have great theories, and you listen to them, people are entitled to them, and good luck to them, theories do work for some people.”

One rule Harvey did learn through the 1970s and 1980s was that breeding and owning is not a reliable money-making business. “I’ve had lots of dry runs, lots. I hate losing. To race ten horses and none of them win, I think I’ve got to give this away. But I don’t. Then I get one good one and, ha!, it’s all forgotten. The good thing is it keeps you very humble.”

Trading was a different matter. In the 1990s, after a recession in the industry, Harvey and Singleton bought the Magic Millions auction house on the Gold Coast. It quickly turned around and became a solid cash machine, expanding throughout Australia. Harvey and his wife, Harvey Norman CEO Katie Page, bought out their partners and have owned Magic Millions outright since 2011.

“I’ve always loved buying and selling,” he says, and he looks on Magic Millions as a source of comfort while, as an owner and breeder, he has been through the inevitable ups and downs.

But it is still breeding and racing, with their infuriating unknowns, that fire him up.

“If there’s no thrill in winning, you’re not going to do it. That doesn’t change at all. You’re just as thrilled as the previous time, it doesn’t seem to diminish. Do I get as big a thrill as the person who has just the one big win in their life?

“You see vision of how excited they get, ten of them hugging each other, high-fiving and having another drink. I can’t get that excited when I have five per cent of a horse and it wins a country race. But the more you’ve got, the more success you’ve had, you need still more of it. I’m very happy with any winner, but then I need three or four. That’s why I have lots of horses. It’s an addiction, there’s no question about it.”

Harvey has an unusual method — or lack of method — in where to send his racehorses to be prepared for the track. He sells off anywhere between all and nothing of a horse he has bred, but if he has any say in where it is prepared, he disperses his gallopers among dozens of trainers. At present, he has an estimated 150-plus horses in work with more than 60 trainers.

“Everyone that’s ever been like me has ended up having their own training complex and their own trainers,” he says.

“Nobody does it like me. But I like people, and I like seeing people come from nothing to something. Hundreds of people over the years, I’ve changed their life by giving them an opportunity. You get a young trainer, or an old trainer, and they say, ‘Without you, I wouldn’t still be training.’”

It must be impossible to say no to this Santa Claus of the track, and Harvey admits almost nobody ever does. He gives trainers several chances before he will take horses off them. “It’s very rare that I take a horse away. When I’ve done that, I give them another horse later on. A lot of people won’t even allow a trainer one mistake.

:If they break an agreement we’ve had, I might take the horse off them, but I’ll say, ‘Give me a ring one day when you’ve decided to be honest. If not, you go your way, I’ll go mine’

Normally I just say, ‘Don’t do that again — if you do that again, we’re going to have a problem’ I try to be kind and give people more than one go.”

Twenty years ago, one of those grateful battlers was a young Chris Waller, who received a mare called Snowdropping from the Harvey stock. Today, Harvey is just as proud of the start he gave the champion trainer as the help he gave to a lifelong journeyman such as Pat Webster, and pretty much everybody else in between.

"I might take the horse off them, but I’ll say, ‘Give me a ring one day when you’ve decided to be honest. If not, you go your way, I’ll go mine’"

There is a continuity in that method, at least, between racing and retail. Harvey may be across the detail, as the reams of paper and the proximity of his racing manager McDonald attest, but he couldn’t keep so many plates spinning if he was a control freak. (Sporting control freaks play tennis or snooker, while racing, with all its uncontrollables, would only keep them up in a cold sweat all night.)

“I’m a big delegator,” he says. “You can’t build a big business if you’re untrusting. I know people who were better at their retail operations than me, and who were successful, but because I trust people and delegate, I could open more stores and make more money. It’s no different in the horse business.”

Four days after our interview in October 2022, he would have Alligator Blood running in the W. S. Cox Plate and later that spring he would win the Champions Mile at Flemington.

In 2023, Alligator Blood would go on and win three further Group 1 races in Harvey’s colours, taking his career prizemoney to over $8 million.

It was a typical Harvey story: he bred the colt and sold it as a yearling to Allan Endresz at the Magic Millions sale in 2018 but, after Endresz’s undisclosed bankruptcy, Alligator Blood became temporarily ineligible to race in Victoria. Harvey stepped in and bought a majority share. The horse has been a money-spinner ever since.

It was a winning gamble without being a punt. For Harvey, the satisfaction of what he has just achieved is soon eclipsed by thoughts of what is coming next. Winning is good, but his aims are as humble as you would expect from someone who has lost more than he has won. “I don’t really have any (unfulfilled goals). I’m just trying to breed and race the best horses I can.”

The article was written for a previous edition of the Aushorse magazine and has been republished with permission, with some minor updates. The 2024 edition of the Aushorse magazine is now available.