‘Thinking the worst and hoping for the best’ – Studmaster’s rescue mission amid flood devastation

Neck-deep in rising floodwaters to save his broodmares and newly weaned foals, Craig Ruttley feared the worst. But the principal of Glenthorne Park Thoroughbreds says he is one of the lucky ones among the devastation left by last month’s floods in the mid-north coast of NSW.

Soon after being woken in the middle of the night by his phone, Craig Ruttley turned on the surveillance cameras scanning his property that backs onto the Manning River, south of Taree.

Days of rain when more than 600mm fell between May 20 and May 23 had put the district on edge. Flood warnings are an accepted part of living in the area but a call Ruttley received from a concerned neighbour changed everything.

The river had burst its banks. Floodwaters were rising fast, and they needed somewhere to seek refuge.

What Ruttley saw on the security footage also revealed a potentially grim outcome for his Glenthorne Park Thoroughbreds stud, his family home and the horses he agists on 150 acres near Taree.

Glenthorne Park has been in the Ruttley family for almost two decades. There has been flooding before, but nothing like this.

“It was the worst I’ve ever seen and people who have lived here all their lives said it’s the worst they’ve seen,” Ruttley told The Straight.

“During the night we got something like 300 millimetres of rain. It just flogged down, flogged down.

“When I pointed the cameras down towards the river, the water was about maybe 50 metres from the house.”

In the space of 12 hours, Ruttley’s life was about to be turned upside down. He told his wife Samantha and his children Isabelle and Isla to start preparing to leave.

“I said to them, ‘if this keeps coming, we’re going under’,” Ruttley recalled

By daylight, and with the help of his eldest daughter Isabelle, Ruttley started moving stock – horses and cattle – to higher ground on the property. There was worse to come.

The water kept rising. It was relentless and the horses he thought had been taken to safety were now in danger of being swept away.

“That afternoon, there were some mares and foals in a paddock where I thought the water was getting a bit deep for them and I had to get them up even higher,” Ruttley said.

“So I had to go and bring them up even further towards the house, right next to the house. And I had to swim them up.”

In a desperate situation, Ruttley was in neck-deep water that was “freezing cold” and some of the foals were struggling.

“Some of them would put their head up in the air and stuff like that. So I thought, ‘I’m going to lose them if I don’t go and get them out’,” Ruttley said.

“I started grabbing a few. I’ve got probably 12 mares and foals here at the moment and it took me three or four goes.

“I’d get one and then a few would stay before you’d get two or three who would follow and then you get another one and another two or three would follow them.”

As is often the case, debris and wildlife present further challenges associated with floodwaters.

For Ruttley, a few snakes swimming for their lives were almost inconsequential to the spiders he encountered during the rescue.

“There were a million spiders in the water. It was just spiders everywhere. I saw a couple of snakes, but nothing, nothing too bad. A couple of black snakes,” he said.

“The spiders … you couldn’t imagine how many spiders there were. It was just like a scene out of a movie. It was ridiculous.

“They were all clinging to the fence lines and the gates … all just covered in spiders.”

As night fell, it was also time for Ruttley to evacuate, knowing there was nothing more he could do to ensure the safety of his livestock. All of his horses and most of the cattle had made it to the highest ground possible.

With all access roads cut off, Ruttley left the property on a mate’s boat. Others in the area had to be winched to safety from a helicopter.

Staying overnight with family friends, he prepared himself for a scenario like the total devastation that he knew had left people homeless and their farms in ruins.

Up to 80 sheep belonging to his next-door neighbour drowned and Ruttley held grave fears for his broodmares and their newly weaned offspring.

“I honestly thought I’d come back and the house would be under. I didn’t know what animals I’d have left,” he said.

“You think the worst and hope for the best.”

It turned out Ruttley and his family were among the lucky ones.

A water line shows the flooding came within a metre of the property’s house before it receded to the river. They lost some cattle but the horses were safe, including their stallion Sebring Sun, who is getting winners from limited books of mares.

Ruttley’s prized bull, left to fend for himself, also survived “but when I found him he wasn’t in the paddock that I left him in”.

He expects it will take a year for the farm to recover properly.

But he can at least look forward to spring with Sebring Sun, who is generating interest with smaller breeders with a promising runners-to-winners strike-rate to match Ruttley’s enthusiasm for the stallion’s bona fides as a sire.

“For us, our stallion is our bread and butter,” he said.

“From September through to December is the time for us when it cranks up and you hope you can get a decent amount of mares to him to carry us through the year.”

For his neighbours, the future is less certain – if there is one at all. Most insurance companies don’t provide flood cover in the region. Premiums from those who do can cost as much as $80,000 annually.

“What have I lost compared to a lot of people? I’ve lost a bit of stock, but I didn’t lose any horses,” he said.

“I’m still lucky because I’ve got friends down the road and they’ve lost their house, they’ve lost their animals, they’ve lost their tractors, they’ve lost their cars.

“They’ve lost everything. It’s like a war zone. Unless you see it with your own eyes, you can’t imagine the devastation.

“By the time it dries out and you do your fencing that you’ve got to fix, for me it’d be at least 12 months.

He expects it will be years for them to get back to some sort of normality.

“You go down the road and all the fences are washed away. There’s nothing there. It’s just barren,” he said.

Ruttley wasn’t the only one in the thoroughbred industry around the mid-NSW north coast who was affected.

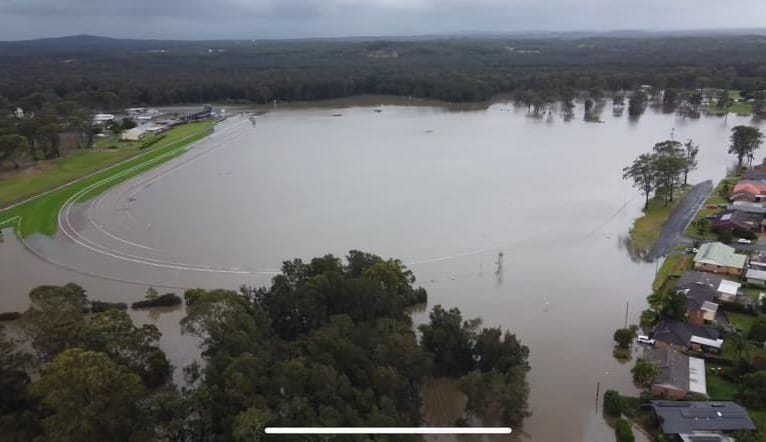

Taree racehorse trainers Tony Ball and Glen Milligan are also in recovery mode from the flooding that has been described as a “once-in-five-hundred-year” event and inundated the racecourse.

They have been helped by a Racing NSW emergency funding package and their morale received a much-needed boost when they both trained winners when the Manning River Race Club (MRRC) returned to racing at Taree last week.

“Everyone tells you it’s a flood like no other. You go back and look at the stats of the 1929 flood and it’s outdone that one,” MRRC chief executive Damien Toose said.

“On the Tuesday morning, seeing the size of the flooding and the way it was running, you were just never too sure where it was going to end.

“With the facility here, we’re a little bit lucky in that obviously the track was underwater, but it’s built on a bit of a slant. So, the main concern was definitely the welfare of the horses.

“As much as we were affected by the flood, it was a blip on the radar here at the track … the damage was minimal.

“But you look at the destruction north of Taree and you go through Taree itself and it’s a community which is definitely feeling the effects and the pain of what’s gone on.”

When the time is right, the MRRC is ready to play a role in the rebuilding process.

“The committee will make sure that we can look after our trainers by doing things to make sure everything’s all right. The trainers particularly, they just want to get back with their horses and get back into the motion of racing,” Toose said.

“We’ll let everyone get back into the stride of things and then, looking ahead, we’ll look to do something for the industry, but more so for the wider community when we can.”

Ruttley says there will be ongoing costs for his business as he tries to mitigate the damage to the pasture caused by saltwater.

“The grass that is there now will not be the best nutrition. With racehorses, what you put into them is what you get out of them,” he said.

“So my feed costs are going to go up now and there will be maintenance, unnecessary maintenance that I didn’t really need to do.

“But compared to my friends down the road, I can’t complain. I can’t whinge.”